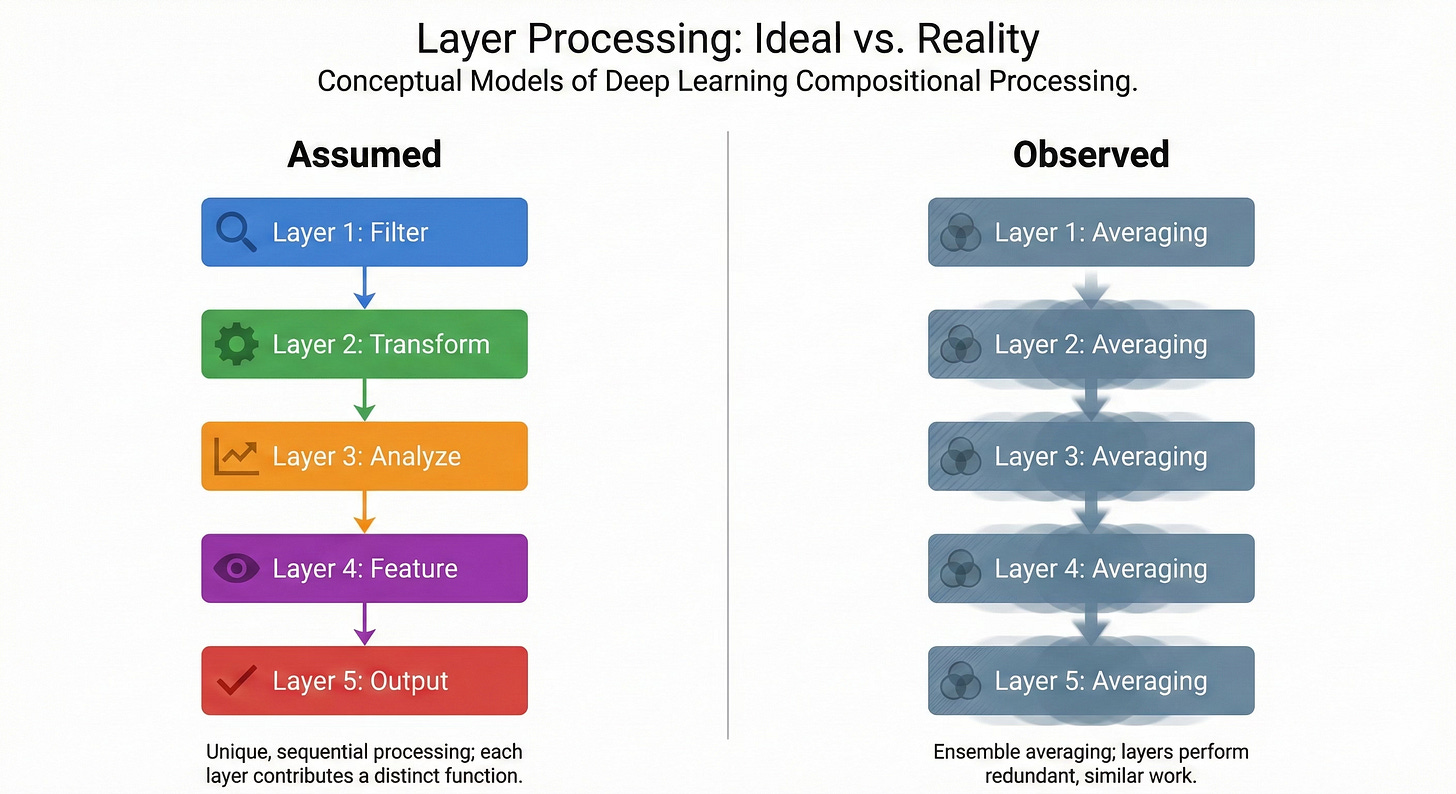

In 2016, a paper Residual Networks Behave Like Ensembles of Relatively Shallow Networks published by Veit et al. showed that a 110-layer ResNet doesn’t actually use 110 layers of compositional processing. Most of the gradient flows through paths only 10 to 34 layers deep. The rest contribute almost nothing. The network isn’t a deep pipeline building increasingly abstract representations. It’s an implicit ensemble of shallow subnetworks, and deleting individual layers barely moves the output. The reviewers at the time found the experiments convincing but pushed back on the framing. ResNets “behave like” ensembles. Whether they are ensembles remained open.

That question sat unanswered for nearly a decade. And the field moved on. Transformers arrived, the race to stack more layers intensified, and we built models with trillions of parameters on the assumption that deeper means more capable. Layer by layer, abstraction by abstraction, the story went: depth is where compositional reasoning happens. But, was it?

Evidence accumulated quietly. Stochastic depth training (Huang et al., 2016) randomly dropped entire layers during training and found that performance improved. On a 1202-layer ResNet, it cut test error from 7.93% to 4.91%. If layers were performing indispensable sequential computation, randomly removing a quarter of them should be catastrophic. Instead, it helped. ALBERT (Lan et al., 2020) took this further into transformers, sharing all parameters across every layer. Attention weights, feedforward weights, everything identical at every depth. Performance dropped by roughly 1.5 points on average benchmarks. If each layer were computing something unique, parameter sharing should have been destructive. It wasn’t.

Then the LLM era made the redundancy impossible to ignore. ShortGPT (Men et al., 2024) removed layers from GPT-style models ranging from 7B to 70B parameters and found you can drop up to 40% before hitting a performance cliff. Not 5% but 40%! A 13B model with 10 of its 40 layers removed retained 95% of its MMLU score. With 22 layers removed, the remaining 5.6B-parameter stub actually outperformed the full LLaMA 2-7B. Your Transformer is Secretly Linear (Razzhigaev et al., 2024) explained why consecutive transformer layers produce representations with a Procrustes similarity of 0.99 out of 1.0. Most layers are performing something very close to an identity transformation. The residual connection dominates, and each layer’s actual contribution is a small perturbation on top.

In October 2025, On Residual Network Depth closed the theoretical loop. The authors proved mathematically that a residual network with n blocks decomposes into a sum over all 2n subsets, each representing a computational path through the network. Increasing depth doesn’t increase compositional capacity. It expands the ensemble. Veit’s observation from 2016 wasn’t a metaphor. It was a mathematical fact waiting for its proof.

So by the start of February 2026, the groundwork was laid. The question was no longer whether transformer depth works through ensemble averaging. It was how far the implications reach.

This week answered that.

Inverse Depth Scaling From Most Layers Being Similar (Liu, Kangaslahti, Liu, Gore) quantified the relationship directly. Analyzing Pythia, Qwen-2.5, and OPT, they decomposed the standard neural scaling law into separate depth and width components. The depth-dependent loss scales as D-0.30, meaning each additional layer buys you diminishing, sub-inverse returns. And the reason is exactly what the pas papers predicted: most layers perform functionally similar transformations, and stacking them reduces error the way averaging reduces variance. Not through composition, but through the central limit theorem.

The authors put it precisely: the regime is “inefficient yet robust.” Ensemble averaging is hard to break (drop members and the average barely shifts), but it’s a poor use of parameters. If 70 of your 80 layers are doing roughly the same computation, you’re paying for 80 layers of compute to get the effective capacity of something much shallower. They pin the blame on residual connections specifically, arguing that the skip-connection architecture biases networks toward this averaging regime, and current training procedures don’t push them out of it.

If that’s the full picture, though, it raises an uncomfortable question. If most layers are redundant copies doing the same thing, then where does capability actually live? Is it built through deep processing, or is it already present in the pretrained weights, distributed broadly across a network that mostly uses its depth for noise reduction?

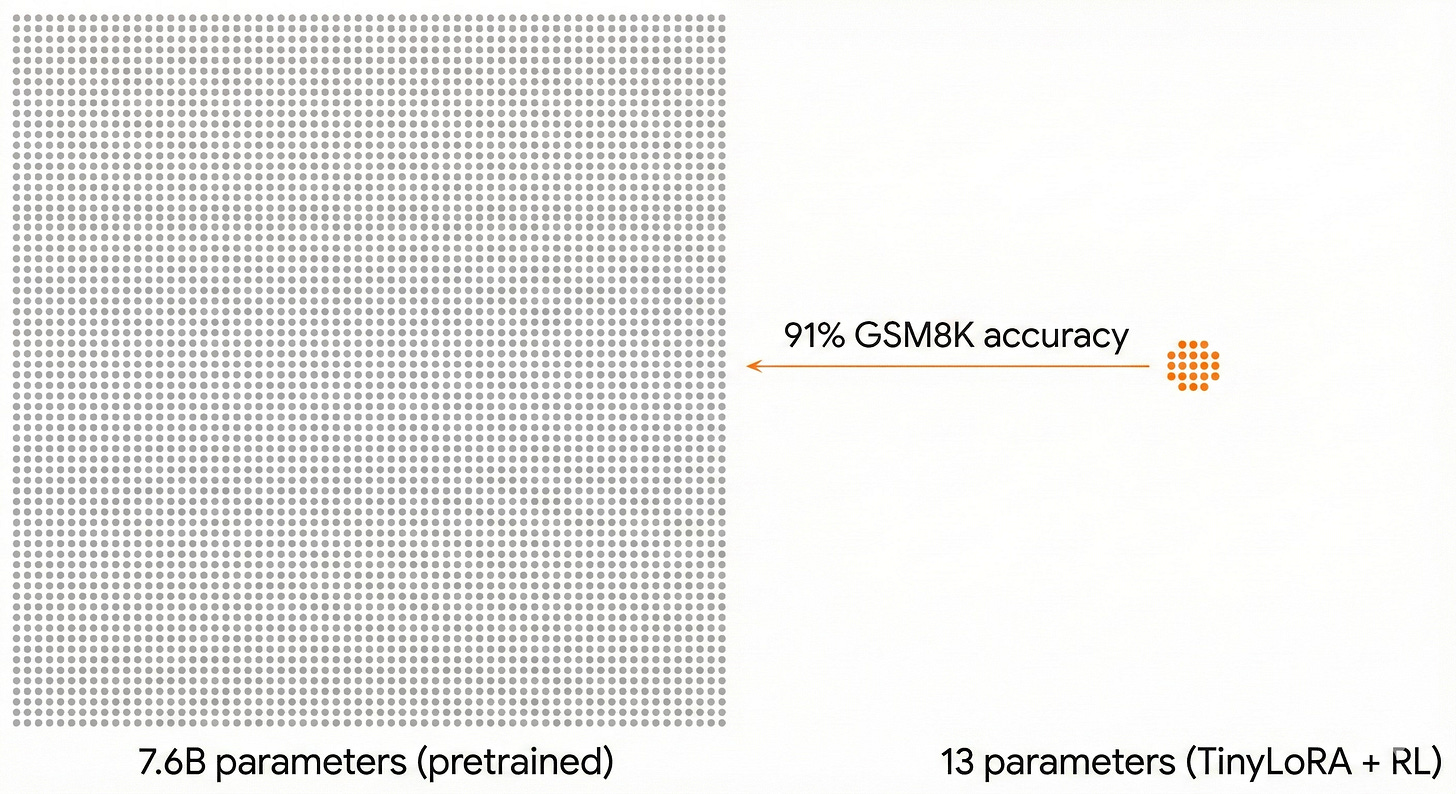

Learning to Reason in 13 Parameters paper introduces TinyLoRA, a method for scaling low-rank adapters below rank 1. Using their parameterization on Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct, they train exactly 13 parameters (26 bytes in bf16) with reinforcement learning (GRPO) and achieve 91% accuracy on GSM8K. With 196 parameters, they recover 87% of full fine-tuning’s improvement across six math benchmarks including AIME and AMC. The gap between adjusting 13 weights and adjusting 7.6 billion is remarkably small.

This result doesn’t make sense under the compositional depth model. If reasoning were built through deep sequential processing, unlocking it would require modifying the computation at multiple stages. You’d need to reshape the pipeline. But it makes perfect sense under the ensemble model. If reasoning capability is already distributed across a broad, redundant ensemble of similar computations, then a tiny perturbation can shift the ensemble’s collective output without needing to modify any individual member substantially. The capability isn’t missing. It’s already there, just slightly misaligned, and aiming it correctly requires almost nothing.

However this only works with RL. Supervised fine-tuning requires 100 to 1000x more parameters for equivalent performance. SFT barely outperforms the base model below 100 parameters. The explanation fits neatly: RL receives sparse but clean signal (correct or not), and through resampling, it amplifies features correlated with reward while uncorrelated variation cancels. It doesn’t teach reasoning. It locates the reasoning that’s already there. SFT, by contrast, tries to absorb all the details of the demonstration, useful structure and noise alike, and that requires a much larger update surface.

So depth provides redundant averaging, and capability is latent rather than built. That accounts for two of the three dimensions of a transformer. What about the third? If depth is mostly doing the same thing at every layer, does width tell a different story?

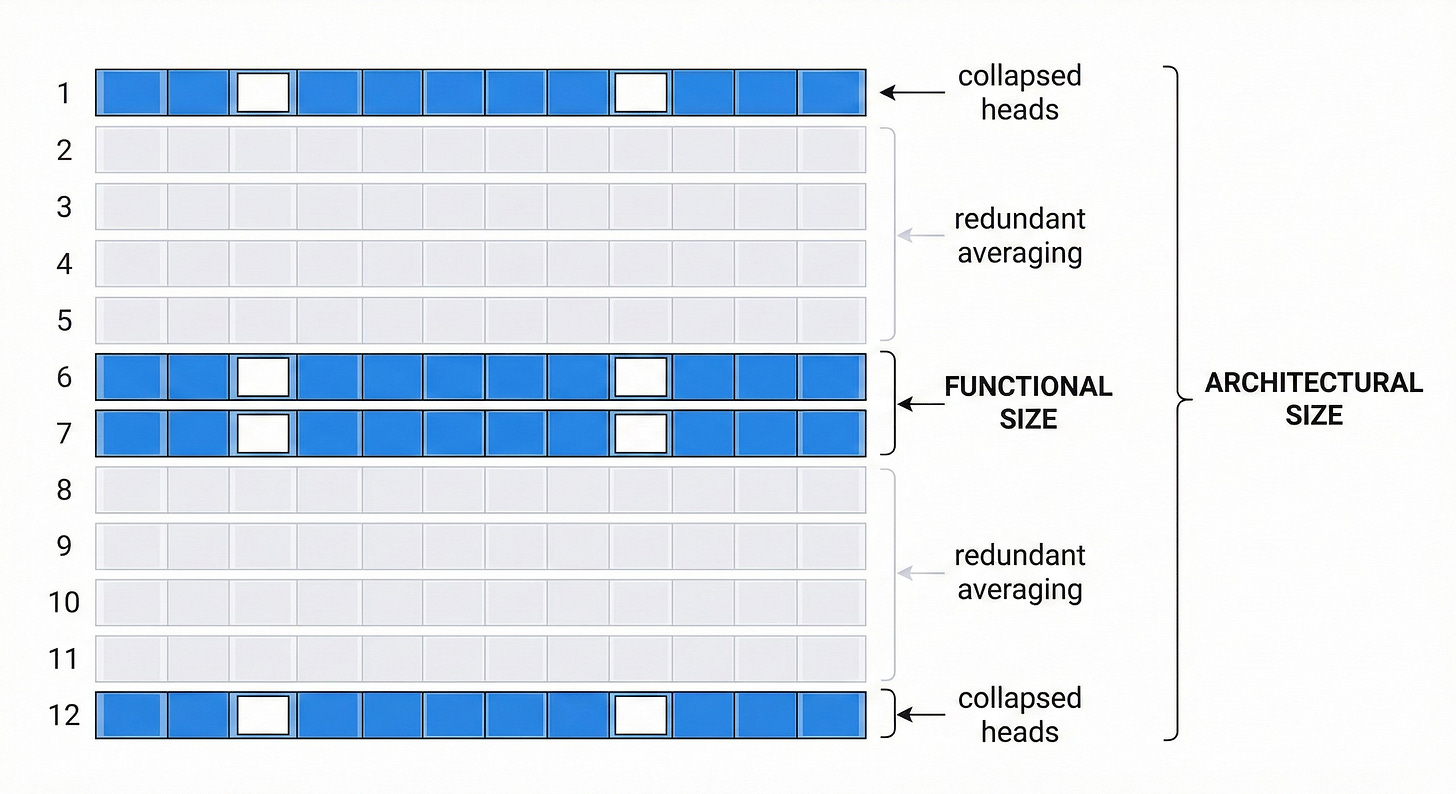

Attention Sink Forges Native MoE in Attention Layers reframes a well-known phenomenon to address exactly this. LLMs famously assign disproportionate attention to the first token, a behavior called the attention sink. The standard interpretation treats this as an artifact. This paper show it’s actually a routing mechanism. The fraction of attention weight not absorbed by the sink functions as an implicit gating factor, mathematically equivalent to a Mixture-of-Experts router. Individual attention heads serve as experts, and the sink determines which ones contribute to any given input.

This interpretation explains something practitioners have observed for years: head collapse, where only a subset of attention heads actively contributes while the rest go dormant during generation. Under the MoE framing, this is expert collapse by another name. And the numbers are striking: over 25% of attention heads can be zeroed out with no meaningful accuracy drop. Worse, head collapse intensifies with scale. Larger models with more heads show lower head utilization rates.

The depth and width findings combine into a picture that should concern anyone designing or deploying large models. Depth provides redundant averaging rather than compositional processing. Width provides expert selection, but without proper load balancing, a quarter or more of the experts go unused. Modern LLMs may be simultaneously too deep (layers averaging rather than composing) and too wide (heads collapsing into dormancy). The result is a model that’s architecturally large but functionally much smaller than its parameter count suggests.

What this doesn’t mean is that depth is useless, or that transformers should be shallow. Ensemble averaging is robust. It works. And some tasks clearly benefit from the error reduction it provides. The claim is narrower but more consequential for how we build and train: we’ve been scaling depth under the assumption that it enables compositional reasoning, and the evidence now clearly points to a simpler, less efficient mechanism.

For architecture design, the open question is whether networks can be made to use depth compositionally rather than for averaging. The inverse depth scaling paper identifies residual connections as the likely culprit. Whether alternatives like state-space models or hybrid recurrent architectures escape this trap remains unclear. For fine-tuning, TinyLoRA raises a practical question about whether most LoRA configurations (ranks 8 to 64) are massively over-parameterized for tasks with verifiable rewards. For inference efficiency, the attention sink MoE finding suggests that sparsity in attention heads is a feature to be leveraged, not a bug to fix, and that load-balancing losses during training could extract more value from existing parameters without adding either depth or width.

The decade-long arc from Veit 2016 through this week’s papers tells a consistent story that the field was slow to absorb. We built the largest models in computing history on the assumption that depth builds capability. The evidence says depth mostly builds redundancy, the capability was already there, and we’ve been paying an enormous computational tax to average our way to marginally better answers.

Whether the next generation of architectures can actually do something different with their depth is the question these papers leave on the table.