Over the past several years, we have moved from the machine learning era through the large language model era and into what researchers now call the agent era. But we did not arrive here overnight. A series of research contributions, each building on the last, have made agents progressively more capable. This article traces that timeline through the papers that shaped today’s autonomous systems.

The Architectural Foundation

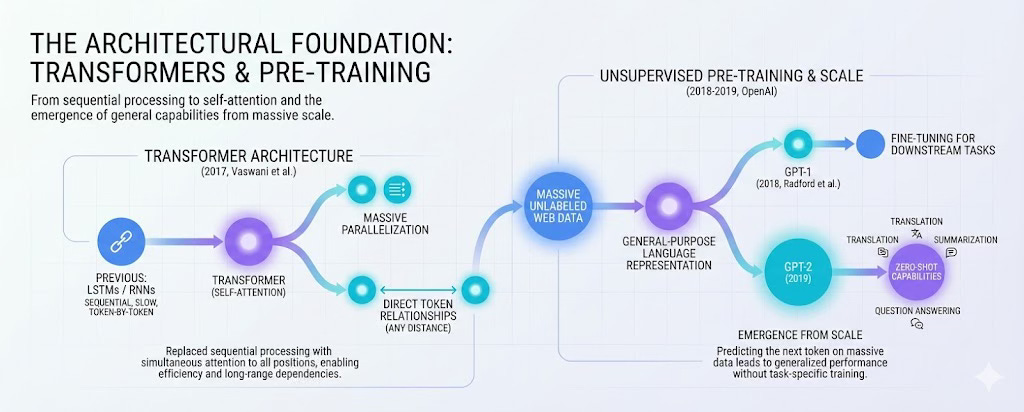

The first major shift came in 2017 with the introduction of the Transformer architecture in Vaswani et al.’s paperAttention Is All You Need. Before this, models like LSTMs processed sequences one token at a time, which made training slow and made it difficult to capture relationships between distant words. The Transformer replaced this with a self-attention mechanism that allowed the model to attend to all positions in a sequence simultaneously. This enabled massive parallelization during training and gave models a way to directly relate any two tokens regardless of their distance in the input. This architecture now serves as the foundation for nearly every modern language model.

Researchers then found that training these models on large amounts of unlabeled web data through unsupervised pre-training could produce general-purpose representations of language. In 2018, Radford et al. at OpenAI demonstrated this with GPT-1, showing that a model pre-trained on raw text could be fine-tuned to perform well across a range of downstream tasks. The following year, GPT-2 took this further. Without any task-specific fine-tuning, GPT-2 could perform translation, summarization, and question answering in a zero-shot manner. The model was simply predicting the next token, yet something more general about language seemed to emerge from scale.

Scaling and the Emergence of In-Context Learning

In 2020, Brown et al. released GPT-3, scaling the architecture to 175 billion parameters. The paper demonstrated that at sufficient scale, models exhibit few-shot learning: they can perform new tasks given just a handful of examples in the prompt, without any gradient updates. This was a significant finding. It suggested that larger models were not just incrementally better at the same things. They appeared to acquire qualitatively different capabilities.

However, scale alone did not make these models reliably useful. A model could generate fluent text but still produce outputs that were unhelpful, untruthful, or misaligned with what the user actually wanted.

Aligning Models with Human Intent

The problem of alignment had been studied in other domains. In 2017, Christiano et al. introduced a method for training reinforcement learning agents using human preferences rather than hand-designed reward functions. The key idea was to learn a reward model from human comparisons of agent behavior and then optimize against that learned reward. At the time, this was applied to simulated robotics and Atari games.

The technique found its way into language modeling through work like Stiennon et al.’s 2020 paper on learning to summarize with human feedback, which showed that optimizing for human preferences produced summaries that people preferred over those from supervised baselines. This line of work culminated in 2022 with Ouyang et al.’s InstructGPT paper. By combining supervised fine-tuning on human demonstrations with reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), they produced a 1.3 billion parameter model that human evaluators preferred over the 175 billion parameter GPT-3 about 85% of the time. The result was striking: a much smaller model, when properly aligned, could outperform a vastly larger one on the metrics that mattered to users.

This mattered for agents because an agent that cannot reliably follow instructions is not particularly useful. The RLHF pipeline established a practical way to make models more controllable.

The Evolution of Reasoning

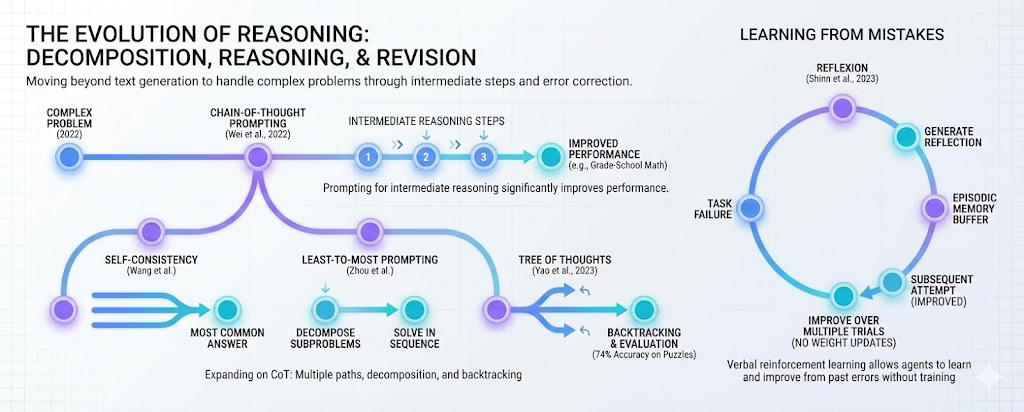

For an agent to handle complex problems, generating text is not enough. It needs to decompose problems, reason through steps, and revise its approach when something goes wrong.

A significant step came in early 2022 with Wei et al.’s work on chain-of-thought prompting. The idea was simple: instead of asking the model to produce an answer directly, you prompt it to show its intermediate reasoning. On arithmetic, symbolic reasoning, and commonsense tasks, this led to substantial improvements. A 540 billion parameter model with chain-of-thought prompting achieved results on grade-school math problems that surpassed fine-tuned models designed specifically for that domain.

Later work expanded on this foundation. Wang et al.’s self-consistency method sampled multiple reasoning paths and selected the most common answer, which improved reliability. Zhou et al.’s least-to-most prompting decomposed hard problems into simpler subproblems and solved them in sequence, with each solution informing the next. By 2023, Yao et al. introduced Tree of Thoughts, which allowed models to explore multiple reasoning branches, evaluate their promise, and backtrack when needed. On certain puzzles where standard prompting achieved around 4% accuracy, Tree of Thoughts reached 74%.

Another direction involved learning from mistakes. Shinn et al.’s Reflexion (2023) gave agents a form of verbal reinforcement learning: after failing at a task, the agent would generate a reflection on what went wrong and store it in an episodic memory buffer. On subsequent attempts, it could retrieve these reflections and avoid repeating the same errors. This allowed agents to improve over multiple trials without any weight updates.

Closing the Loop: Reasoning Meets Action

The work described so far treated language models as reasoning engines operating on text. But an agent that only thinks is limited. It cannot verify facts against the world, run code, or interact with external systems.

The ReAct framework, introduced by Yao et al. in late 2022, addressed this directly. ReAct interleaved reasoning traces with actions. The model would generate a thought about what to do, execute an action like querying a search API, observe the result, and then reason about the next step. This loop allowed the agent to ground its reasoning in retrieved information rather than relying solely on what was encoded in its parameters. On knowledge-intensive tasks, ReAct reduced hallucinations and improved accuracy compared to chain-of-thought alone.

ReAct is often considered a turning point in the field. It unified two threads that had been studied separately: reasoning and acting. Most modern agent frameworks are built on some variant of this pattern.

Grounding in External Knowledge and Tools

The problem of grounding had also been approached from another angle. In 2020, Lewis et al. introduced

Retrieval-Augmented Generation, which combined a neural retriever with a sequence-to-sequence generator. Given a query, the system would first retrieve relevant passages from a corpus, then condition generation on those passages. This allowed models to access information beyond what was stored in their parameters and produce outputs that were more factually grounded. RAG set the conceptual foundation for how agents could interface with external knowledge bases, and the approach has since become standard in production systems.

On the tool use side, models began learning to call APIs directly. Nakano et al.’s WebGPT (2021) trained a model to navigate the web using a text-based browser, submitting queries and following links to gather information for answering questions. Chen et al.’s Codex (2021) demonstrated that models fine-tuned on code repositories could write programs to solve problems, effectively using a Python interpreter as a reasoning tool.

Schick et al.’s Toolformer (2023) pushed this further by showing that models could learn tool use in a self-supervised way. Given only a few demonstrations of API usage, the model learned when to invoke calculators, search engines, or translation systems, and how to incorporate the results into its generation. Crucially, this happened without explicit human annotation of every instance where a tool should be used. The implication was that tool use could potentially scale without proportional annotation effort.

Memory Beyond the Context Window

Standard language models operate within a fixed context window. Once a conversation exceeds that limit, earlier information is simply dropped. For agents that need to maintain state over long interactions or remember facts about users across sessions, this is a significant constraint.

Park et al.’s Generative Agents paper (2023) introduced a memory architecture designed for believable long-term behavior. In their system, agents maintained a memory stream of observations stored as natural language, periodically synthesized these into higher-level reflections, and retrieved relevant memories when planning actions. They instantiated 25 agents in a simulated town environment, and these agents exhibited emergent social behaviors like spreading party invitations and coordinating meetups, all without explicit scripting. The architecture demonstrated that combining memory, retrieval, and reflection could produce coherent behavior over extended time horizons.

Packer et al.’s MemGPT (2023) took inspiration from operating systems. They introduced a tiered memory system where agents could move information between a limited main context (analogous to RAM) and an external archival store (analogous to disk). The agent itself managed what to page in and out through function calls. This gave agents a form of unbounded context, at least in principle, allowing them to maintain coherence across very long conversations.

Multi-Agent Collaboration

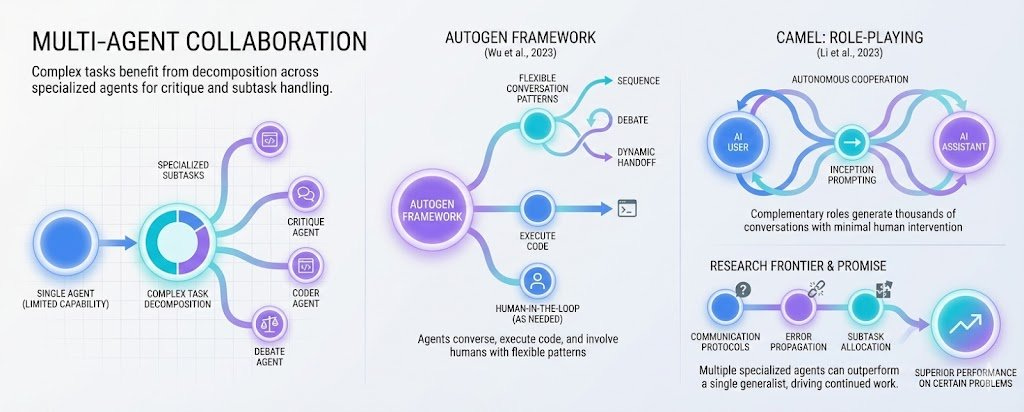

A single agent can only do so much. Complex tasks often benefit from decomposition across specialized agents that can critique each other’s work or handle different subtasks.

Wu et al.’s AutoGen (2023) provided a framework for building multi-agent applications. In AutoGen, agents can converse with each other, execute code, and involve humans in the loop when needed. The framework supports flexible conversation patterns: agents can work in sequence, debate, or dynamically hand off control based on the task.

Li et al.’s CAMEL (2023) explored autonomous cooperation through role-playing. Using what they called inception prompting, two agents would take on complementary roles (such as AI user and AI assistant) and collaborate on tasks with minimal human intervention. The approach generated thousands of conversations that could be used to study emergent cooperative behaviors.

These multi-agent systems remain an active area of research. Coordination introduces new challenges around communication protocols, error propagation, and how to allocate subtasks. But the basic premise that multiple specialized agents can outperform a single generalist on certain problems has shown enough promise to drive continued work.

Where This Leaves Us

Looking back at this timeline, a pattern emerges. No single paper created today’s agents. Rather, agents arose from the gradual integration of capabilities: attention mechanisms that could handle long contexts, pre-training that produced flexible representations, alignment techniques that made models follow instructions, reasoning methods that enabled multi-step problem solving, tool use that grounded models in external systems, memory architectures that allowed persistence, and multi-agent frameworks that enabled collaboration.

Each layer built on what came before. Chain-of-thought would not have worked without models that already had strong language understanding. ReAct would not have been useful without chain-of-thought to structure the reasoning. Tool use would not have scaled without RLHF-aligned models that could reliably follow instructions about when and how to call APIs.

The current generation of agents represents something like a first successful composition of these pieces. They can reason, act, remember, and collaborate in ways that were not possible a few years ago. What comes next is less clear. But understanding how we arrived here seems like a reasonable starting point for thinking about where the field might go.